Phishing leaves a DMARC trail

Earlier this year The Anti-Phishing Working Group (AWPG) and dmarcian had the opportunity to look for patterns across data sets to see if anything interesting emerged. We decided to cross reference the IP addresses from APWG’s phishing and malicious IP data sets contained in their eCrime Exchange (eCX) threat data sharing platform, against the addresses in our DMARC reports to see if there was any overlap, and if so to look for patterns. These are the results that we presented at eCrime 2018.

Overview

At dmarcian, we help our customers get their email systems setup with DMARC as well as processing the numerous aggregate and forensic reports that are generated. When a company goes through the deployment process, the first concern when reviewing those reports is making sure that all of the legitimate sources of email claiming to be from your domain are properly configured.

But what about all of those other IP addresses claiming to be sending on behalf of your domain? We get that warm and fuzzy feeling when we turn our policy up to p=reject, knowing that none of those messages are getting through anymore, but what if there is more to be found? We know all of these IP addresses are sending email that isn’t authorized on behalf of the domain…but what if we cross referenced known bad actors against this data to look for patterns? Could we identify internet-wide abuse? Can we see the breadth of an attack, beyond what is visible in an independent system or report?

Data Sources

We talked to APWG and were granted access to the Malicious IP and Phish data sets to see what we could find. The Malicious IP data set comes almost entirely from PayPal as they contribute 99.986% of the currently available data. The Phish data set is smaller but comes from a much wider variety of companies across every industry.

Here is what the data looked like at the time of our analysis.

- eCX Malicious IP: 24 million reports, 8 million unique IPs

- eCX Phish: 3.25 million reports, 130,000 unique IPs

- dmarcian DMARC: 2 billion reports, 18 million unique IPs

The cross section of those sets gave us just over 1 million from Malicious IP and DMARC as well as 20,000 from Phish and DMARC. About 2,000 appeared in all three sets.

Examining Malicious IP Data

From this overlap we can examine both IP addresses and the domains affected. A single IP address can attempt to send email on behalf of multiple domains and each domain could have multiple different authentication results.

When looking at the DMARC results by IP address we find:

- 95.2% Fail both DKIM and SPF

- 4.0% Fail DKIM but Pass SPF

- 0.8% Fail SPF but Pass DKIM

When we pivot and look at the same results by domains affected we find:

- 95.8% Fail both DKIM and SPF

- 4.0% Fail SPF but Pass DKIM

Combining the result of both IP and domains, which we’ll refer to as “Combined Results” going forward we find:

- 95.5% Fail both DKIM and SPF

- 2.7% Pass DKIM but Fail SPF

- 1.7% Pass SPF but Fail DKIM

Consistent takeaways from both? Less than 0.1% of reported Malicious IPs found in DMARC reports pass both SPF and DKIM while more than 95.5% fail both.

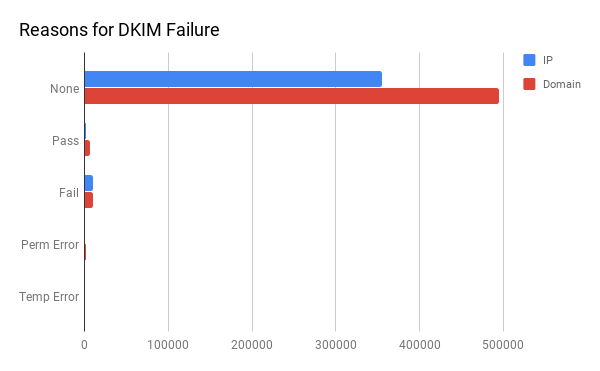

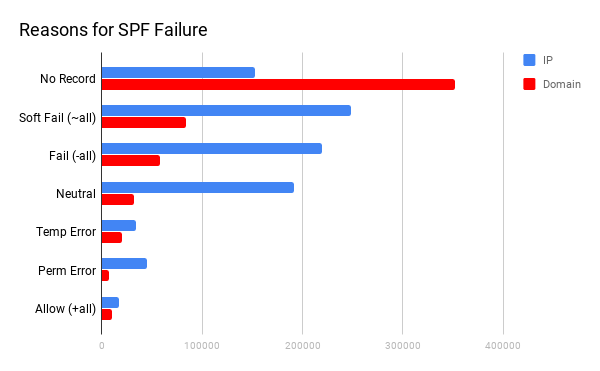

That is the high-level overview. What happens when we look more deeply at the reasons for those results? The vast majority of DKIM results do not even attempt to include a DKIM record, which is expected because without a DMARC record in place a receiving email server has no way of knowing DKIM is even setup for the domain unless it appears in the mail header.

SPF is a domain-wide setting at the DNS level, so even without a DMARC record a receiving email server can check it. Despite that, the domain results show a significant slant towards domains with no SPF record at all. This is also somewhat understandable, since a potential phish can look for domains that lack SPF prior to sending email on its behalf. The IP distribution is more balanced though.

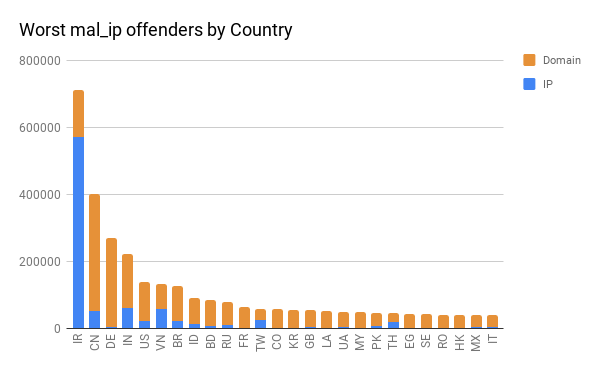

When looking at the origins for these results, we were curious to see the breakdown by country of origin for the worst offenders. We found an interesting distribution here as nearly every country had more offending domains than IP addresses, except for Iran which had more offending IP addresses than the rest of the worst offenders combined. We also broke it down by ASN and found a single ASN in Germany to be the worst offender for domains followed by four from China and six from Iran.

What about Phish?

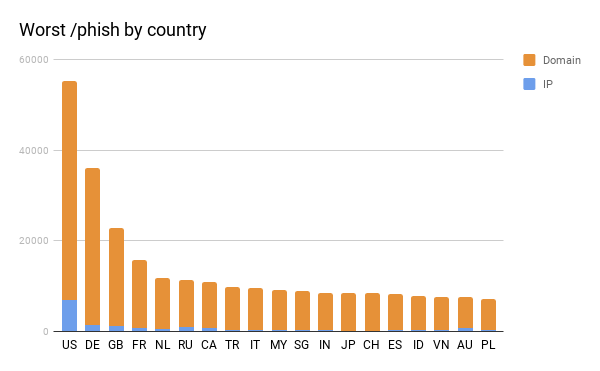

While these numbers were interesting, we also knew that this data was mostly from PayPal so we wanted to take a look at the Phish data to see if a more industry-diverse data set showed similar results. We started by taking a look at the country distribution, which provides a very different picture.

The US is the worst offender here, followed by Germany. Noticeably absent from the data set are both Iran and China. We decided to take a look at the small cross section of both Phish and Malicious IP data and even that small cross section closely mirrors the Phish results that we see above.

Knowing that there are significant differences in sources, we were curious how that would affect the email authentication results? As it turned out, the difference was fairly significant. Across domains and IPs for the Malicious IP data set we saw a 95.5% fail rate for both SPF and DKIM.

The phish results, however:

- 66.2% Fail both SPF and DKIM

- 32.7% Pass DKIM and Fail SPF

- 0.7% Pass SPF and Fail DKIM

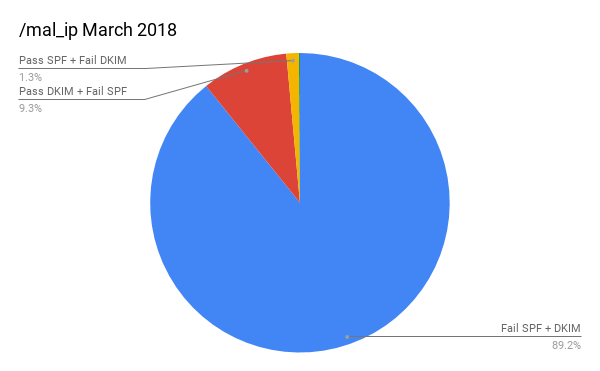

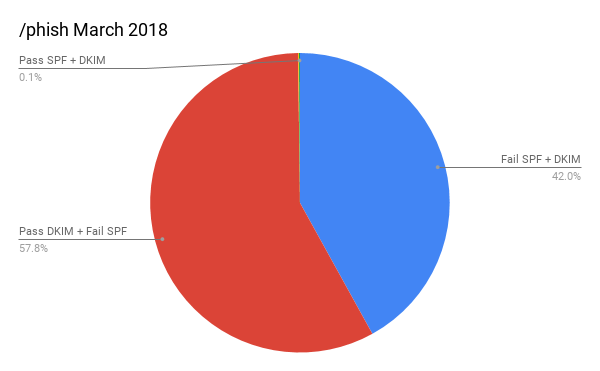

Our first response to this was to wonder if our data set was too broad. After all, DMARC reports change over time as people slowly get things setup, so what if we were to look at a much smaller cross section and focus only on the results for March 2018? Those results were more shocking.

First, the Malicious IP data looks mostly the same but does show a higher rate of DKIM passing.

Phish, however, is much, much worse.

Almost 58% of Phish are actually passing DKIM! Numbers like that can create a lot of speculation about the causes, so let’s take a deeper look before we go down that road.

Forwarders

A subset within this data that we haven’t really broached yet are email forwarders, which are servers that attempt to relay messages. This could be a hosting company where a customer accept email but then forwards to a mailbox provider, a university alumni forwarding address or even a mailbox that is configured to immediately forward to another address.

When we break down the phish results and include known email forwarders:

- 57.8% Passing DKIM but Failing SPF, 99.89% were via forwarders.

- 42.0% Failing DKIM and SPF, 31.17% were via forwarders

< 0.1%

One thing that is consistent across both data sets, even with the more shocking results that we’re looking at is that less than about 0.1% of reported phish or malicious IPs are passing both SPF and DKIM, which is a big win for domains that have implemented strict DMARC policies.

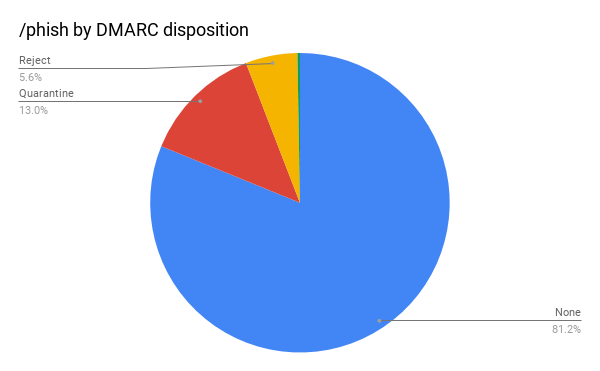

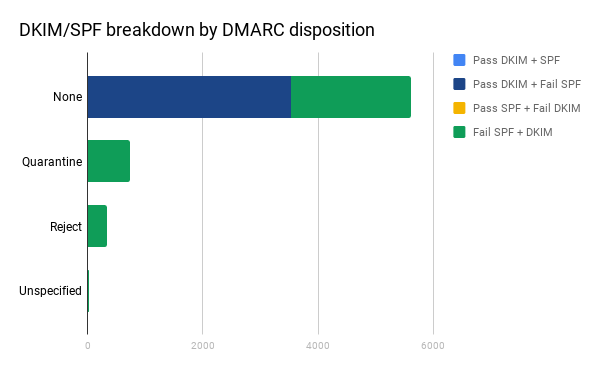

What about the DMARC policies themselves? When you configure DMARC one of the settings is “disposition,” which tells mail receivers what do do with messages that do not pass your rules. These setting can be “reject,” to prevent delivery entirely, “quarantine” to send the messages to spam or “none” to do nothing at all. So what do those phishing results look like, based on the DMARC disposition settings?

Over 80% are set to none. This is worth looking into further because, just like the SPF record, a potential attacker can check a domain’s DMARC record to see if a weak policy is in place before submitting an attack. Let’s combine those disposition results with the SPF and DKIM results to get the complete picture.

All of the results that we saw which were passing DKIM came from domains with a DMARC policy of “none.” This is the point where we can start to speculate a little bit, because if this was simply a normal distribution the expectation would be to see some DKIM passing results in the other sections.

DKIM is interesting because it uses a cryptographic key to sign emails originating from them, with the public version of key listed in the DNS for a receiver to compare against. Cryptographic keys vary by key strength and weaker keys are easier to crack. Back in 2012 a mathematician named Zachary Harris realized that Google was using a weak 512 bit key and made headlines when he cracked it, then sent emails to Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin as each other to demonstrate it. Two days later, Google increased their key strength to 2048 bit. A year later, Gmail started failing DKIM results for keys signed with 512 bit or less.

Best practices for DKIM include periodically rotating those DKIM keys. The longer a key sits unchanged, the longer the potential timeline for a key to be compromised or abused. Despite being a best practice, rotating DKIM keys is not a trivial task, because it involves changes on outgoing email servers in conjunction with DNS records. Many email service providers will automate this task for you since they already control the outgoing email server, by having you set two DKIM records as CNAME DNS entries that point to their DNS. From there, these companies have the ability to set a new key, retire an old one and determine which key is being used with outgoing messages.

SPF at least requires a phish to send a message from somewhere within your allowed range of IP addresses, which could involve compromising an actual machine or a shared email provider. The combination of non-rotated, weak DKIM keys with a DMARC disposition of “none” that would allow them to go through, despite failing SPF creates a potentially appealing target. The results in that last chart would seem to support this theory, with 0% of phish that are passing DKIM coming from domains with a DMARC disposition stronger than “none.” Unfortunately for this report, we were not able to get a breakdown of DKIM key strength.

Patterns for Worst Offenders

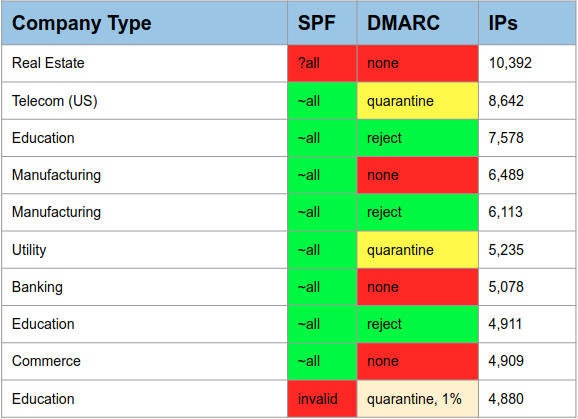

Out of all of the results that we’ve seen, we were curious about the breadth of the SPF/DKIM failures. Were there certain domains that were failing more often? Were certain domains targeted by more IP addresses than others? What did those DMARC and SPF policies look like. The domain names have been obscured to “industry only” for purposes of this next chart, sticking to March 2018 for our time window.

In March, a single Real Estate domain with weak SPF and DMARC policies had over 10,000 IP address sending email on its behalf that were failing both SPF and DKIM. Only 3 of the top 10 have a policy of “reject” and one shows a “quarantine” that should only affect 1% of email sent on its behalf, which is only a small step up from “none.”

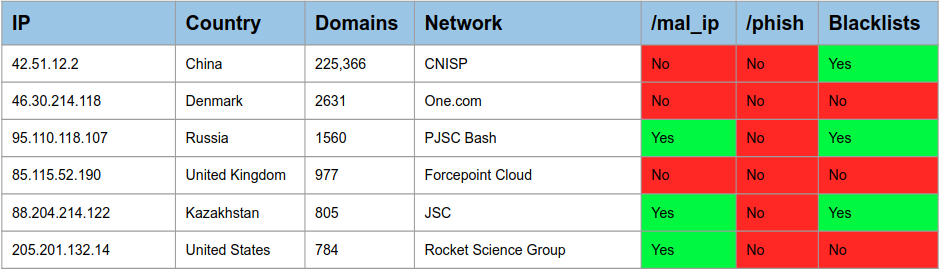

What about the worst IP addresses?

In March, a single IP in China attempted to send email on behalf of over 225,000 domains that failed both SPF and DKIM. This looks to be an anomaly as it far outpaced the next closest. Some of these IP address showed up in the Malicious IP set, while we found others on some existing blacklists, but this does beg the question of whether or not DMARC reports can potentially be used to identify IP addresses that may belong on blacklists themselves. Over the lifetime of results, the top 10 worst offending IP addresses targeted over 30,000 domains each. That is not shown in the chart, we were just curious.

We also checked these IP addresses against some publicly available DROP lists, without seeing much of an intersection. It’s hard to draw much of a conclusion from that, however, as it could just indicate that traffic from those ranges is getting filtered out before it even makes it to authenticity checks.

Conclusions

The results here were very interesting for us. Being able to compare the aggregate results of DMARC reports against known malicious reporting systems showed some interesting patterns.

For us, this translates to three distinct thoughts:

- Strong email practices work effectively to protect your domain across DMARC, DKIM and SPF with less than 0.1% of offenders coming against domains with strong policies.

- The volume of phish traffic passing DKIM but failing SPF is troubling. It creates a strong case for better DKIM policy like rotating keys.

- Moving forward, it does appear that there is some potential value that could help to enhance blacklists and warning systems using aggregate negative results from these reports.

Want to continue the conversation? Head over to the dmarcian Forum.